Dear Sparta,

We say we have Spartan pride. We yell it at football games, print it on T-shirts, and hang it on banners. But do any of us know the full history of the land on which we have built our homes, schools, and churches? How can we have “Spartan pride” if we don’t educate ourselves on the history of our town, and try to do better than those who came before us — try to make it a better place? In light of recent events, namely the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, as well as the subsequent protests, I find it necessary to educate myself — and others — on the history of racism and discrimination in my beloved hometown of Sparta, the rest of Sussex county, and New Jersey as a whole. Without knowing our history, how can we promise to do and be better? We owe it to our black family, colleagues, peers, acquaintances, and ourselves to understand the systemic racism that our town was built on. We owe it to them to do everything in our power to try and understand what it means to be black in America — though we never truly will. We cannot have “Spartan pride” without acknowledging the racism this town and surrounding areas were built on.

I am a white woman. I was born into and still experience an enormous amount of privilege. That being said, I am not authorized to, nor do I want to, speak on behalf of or over the black community. However, I think the inhabitants of Sparta and Sussex county need to know our history — especially our black history.

Without further ado, let’s dive into the racially charged history of our beloved hometown.

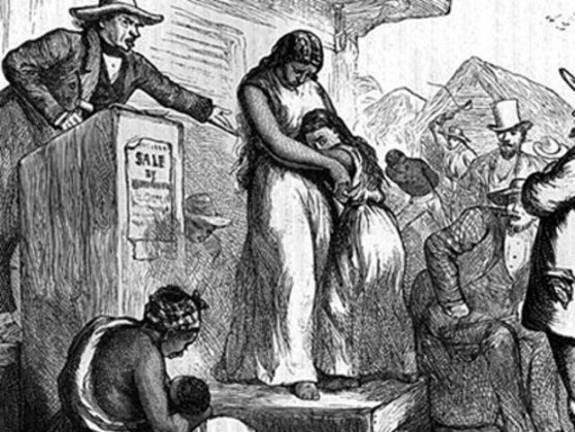

Slavery

Sparta was greeted by its first post-colonial settler in 1778 — Robert Ogden. I want to clarify post-colonial, because this land was originally inhabited by Lenape Native Americans. No white man discovered this land, they merely colonized it. Robert Ogden and his wife built a home and constructed an iron forge, and named their house and farm “Sparta” — such was our town’s humble beginnings. Robert Ogden, our founder and forefather, owned slaves. This town was, quite literally, built on the backs of enslaved African Americans.

This, however, was not the beginning of slavery in our lovely state, as the very first instance of slaveholding was in 1680 in Shrewsbury, N.J.— a quick one-hour drive from us. In the 1780s, following the Revolutionary War, New Jersey banned the importation of slaves, yet allowed the slaves currently held, and those born into slavery, to be kept. New Jersey also did not allow free black individuals to come from elsewhere and settle in the state. Some slaveholders independently granted freedom, but by 1790, 12 years after the founding of our town, there were approximately 14,000 slaves in New Jersey (though the census only counted 11,423).

In 1804, a law was passed that freed all children born into slavery. Women were freed on their 21st birthday, and men were freed on their 25th birthday, but these slaves were often sold to southern states (where there was no such law) just before these birthdays. It wasn’t until 1846 that New Jersey technically abolished slavery — we were the last Northern state to do so. I say “technically” because inhabitants of New Jersey simply reclassified slaves as “indentured servants” for life. Thus, slavery did not truly end in our state until the passage of the 13th amendment to the Constitution — which new Jersey was reluctant to support, though eventually did pass in January of 1866.

It is important to note that when these slaves were eventually freed, the state reimbursed the slaveholders up to $300 per freed slave via the District of Columbia Emancipation Act. The newly-freed black individuals were given nothing, and the slaveholders got richer at the hands of the state. At this point, New Jersey became home to both white and black free individuals, but this was not nearly the end of the hardships of the black community in our state.

Voting rights

After the revolutionary War, New Jersey was unique in that it allowed both women and black individuals to vote. Historians Judith Apter Klinghoffer and Lois Elkis explain that citizens were only required to be free inhabitants of the State who were over the age of majority, had more than fifty pounds of wealth, and had lived in New Jersey for more than six months. Please note that these were strenuous requirements, discrediting many married or poor women, along with many black individuals. This progressive law lasted nearly 30 years, until, in 1807, that portion of New Jersey’s constitution was modified by the passage of a law that “reinterpreted” the constitution’s suffrage clause. A new law was passed that redefined voters solely as adult, white, male, tax paying citizens. Thus, white men were the only citizens voting until, in 1870, the 15th amendment was passed, and New Jersey was prevented from denying the right to vote on grounds of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

This may seem like the end of racially-based voter suppression, but disenfranchisement of black voters followed quickly in the amendment’s footsteps. In fact, as recently as the 1980s, the Republican National Committee hired off-duty policemen to monitor polling places in minority areas of New Jersey and Louisiana as part of a so-called “ballot security” operation. This was widely interpreted to be intimidation of voting minorities.

‘Legal’ and covert discrimination

Though black individuals were given the right to vote, they continued to face hefty discrimination every day. In the 1930s, Long Branch NJ—a beach town I have seen many Sparta residents frequent—passed an ordinance requiring all residents to apply for a pass that would allow access to only one of the town’s four public beaches. Town officials claimed the rule was meant to prevent overcrowding; however, without exception, black applicants were assigned to the same beach and were denied entry to the others. In other words, segregation and discrimination were “legally” enforced.

Another example of covert discrimination was (and still is) the housing market. Lee Porter, a black advocate and activist, was and is a volunteer helping minorities, most of them African American, find homes in New Jersey. In the 1960s and 1970s, she said, discrimination was blatant and based mostly on race. Today, it remains widespread, but it takes more subtle forms, such as real estate agents showing fewer properties and apartments to people of color than to whites.

Similarly, consider the case of Arnold Brown. In 1791, his great-great-great-great-great-grandfather James Oliver was born a slave in Bergen County. Nearly two centuries later, Brown bought a home in Englewood, N.J. He had to sneak inside and tour the home after nightfall so his white neighbors wouldn’t see. This state was built on his ancestors’ backs, yet he was barely allowed to purchase a home in it.

Hate groups in NJ

You may think that all of this discrimination is in the past. After all, no one in our town hates minorities! Think again. As a Sparta resident, I was shocked and disturbed by the recent hate crimes that have come to light. For instance, in November of 2019 a 25-year-old man was discovered to have stockpiled weapons and far-right propaganda, and had talked about shooting up a hospital. Similarly, two months later, New Jersey State Police discovered illegal assault weapons in the backseat of a car in Sussex County. This led to a search of the driver’s home, where they found 17 more firearms, a grenade launcher, and neo-Nazi paraphernalia. These arrests awakened fear that far-right extremism is growing in our small, rural county. New Jersey state Attorney General Gurbir S. Grewal stated, in regards to hate incidents, that with “one hundred percent certainty, the numbers of reports have increased.”

These incidents are increasing, but they are nothing new. In Warren county, following the 2008 election, a family of Barack Obama supporters awakened to find a burned, 6-foot cross on their front lawn. The cross was wrapped in a homemade banner that read “President Obama Victory ‘08.” The burning cross is often the calling card of the white supremacy group the Ku Klux Klan.

Actually, the KKK is nothing new in Sussex County, or its surrounding areas. In 1923, the KKK provided funding that helped found the Alma White College in Zarephath, N.J. This institution —which was not dismantled until 1978 — was run by the Klan to further its aims and principles. Additionally, in Long Branch, The New Jersey Ku Klux Klan held a Fourth of July celebration from July 3–5 1926, which featured a “Miss 100% America” pageant. Unfortunately, the KKK was not all ideology and rallies. On May 10, 1923, the Klan assaulted a boy, accusing him of stealing $50 from his mother in West Belmar. All of these towns are roughly a one-hour drive from my home in Sparta.

You may be under the impression that this hate would never manifest itself anywhere actually near Sparta. Unfortunately, you would be incorrect. From 1937 to 1941, Camp Norland in Andover Township (which, by the way, is a mere 15 minutes away from us), was owned and operated by the German American Bund. The Bund was a group that sympathized with and propagandized for Nazi Germany in the United States. On August 18, 1940, it was the site of a joint rally with the Ku Klux Klan. In short, our town and the surrounding areas are not immune to the hatred and intimidation of minorities — especially the black population — that was present both in the 20th century, and today.

Modern-day racism

Racism and racial discrimination are far from irrelevant in modern-day Sparta, Sussex County, or New Jersey as a whole. There are too many anecdotes to count. The valedictorian of Middletown High School made a video calling out the years of racism and derogatory comments she endured. In response, the students and parents of her high school called for her to be stripped of her title of Valedictorian. In 2019, Nasit Dickerson was subjected to racial slurs as he played in a basketball game at Wallkill Valley Regional High School. Wallkill fans allegedly yelled out “monkey” and the “n-word” while making monkey noises. According to the family, the administration did nothing. After the 2016 election, students in my homeroom and classes chanted “build the wall” before school started. I sat through debates in class about the permissibility of white people saying racial slurs. Our town is the second-least diverse in the state. Our population is roughly 95% white. That does not mean that we get to sit on the sidelines when we see racial injustice. If anything, that means we should be working even harder to achieve equity, to lift up black voices, and to try and set right the centuries of mistreatment faced by minorities — especially the black community.

So, Sparta, now you know a mere fraction of our town, county, and state’s rich history of racial discrimination. I’d like to add that this mini history lesson is far from complete. Pages and pages could be written, full of instances of microaggressions and anecdotes from the past decades, but I wanted to provide a brief and broad summary of the main ideas. To the (most likely) white person reading this: have you realized your privilege? Our ancestors did not face nearly the same challenges as the ones I have outlined above, and we do not face the same challenges as the black community does today. Educating ourselves and learning our history is the first step towards equality, equity, and justice for black communities. If you thought you weren’t racist, hopefully this article has made you realize that you were born into, and profit off of, an inherently racist system that was put into place long before we were born.

I’ll leave you with this: don’t be afraid to say Black Lives Matter. It doesn’t mean your white life matters less. It doesn’t mean you’re discriminating against anyone. What it means is that black individuals have been, and still are, subjected to hardships that we aren’t. Their lives are under attack right now, as seen in the cases of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. Our lives are not.

Black Lives Matter.

Erin Walsh

Sparta High School ‘18

Johns Hopkins ‘22